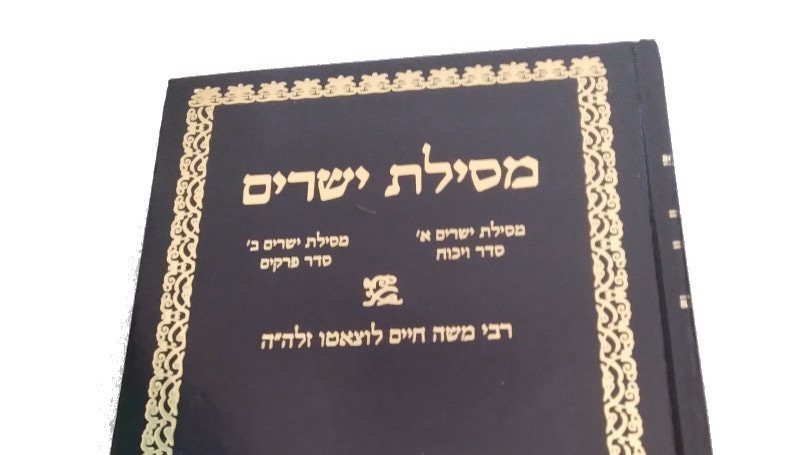

Why Did Ramchal Write Mesilas Yesharim?

Perhaps it really is nothing more than a magnificent guide to Torah perfection

No one who’s spent serious time learning Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato (Ramchal)’s ethical masterpiece Mesilas Yesharim can walk away uninspired. It’s possible to return to sin after being confronted with Ramchal’s powerful arguments, but it won’t be easy.

There’s no doubt that Ramchal gave the world his Mesilas Yesharim out of a genuine desire to have a positive impact. But what was the precise impact he hoped for? A simple reading of the book suggests it’s nothing more than a guide to perfecting our observance of the Torah’s timeless principles. But some claim the book was also designed to subtly introduce esoteric kabbalistic ideas into mainstream Jewish culture.

What would be the point? Well we know that in his youth Ramchal and his peers, following the extended Tzfas tradition in one form or another, were deeply engaged in intense kabbalah study. We also know that many of his earlier seforim were controversial, resulting in his being forced to publicly renounce many of his passionately-held beliefs and teachings. Twice (once in Italy in the early 1730s and again in 1735 in Frankfurt), Ramchal was forced to swear he would cease the teaching and publishing of kabbalistic content.

It’s assumed that Ramchal moved to Amsterdam - where Mesilas Yesharim was eventually written - to escape such restrictions on his activities. So for many it can be difficult to picture Ramchal throwing so much energy into a Torah project without imbuing his work with at least some fruits of his kabbalistic studies.

Curious, I decided to learn through the book once again to see if I could find any evidence one way or the other. At worst, I’ll have spent some time with a supremely beautiful Torah classic. And it wouldn’t kill me to do a little teshuva either. Having spent significant time researching many of the innovative and sometimes shocking beliefs coming from the Ari’s Tzfas community, I had a pretty good idea of what I was looking for.

How did it go?

Armed with some knowledge of the tumultuous events of the Eighteenth Century controversies involving Ramchal and his kabbalah studies, I’ll freely admit that I initially expected to find frequent hints and references to Tzfas ideas. I’ll also freely admit that I was completely wrong. In fact, as far as I can tell, Mesilas Yesharim could, for the most part, have as easily been written and published a century or two before the birth of the Ari, as after. As far as I can tell, there’s barely a trace of kabbalistic influence.

The Simple and Practical Mesilas Yesharim

Let me show you what I mean. First off, Ramchal himself says it pretty much explicitly in the introduction:

“I didn’t write this book to teach people anything they don’t already know, but to remind them of what was already known and blatantly obvious to them.”

Those words would make little sense in describing a book containing mystical secrets. There is, after all, a reason they call kabbalah esoteric.

But, in fact, a lot of the book’s actual content bears out Ramchal’s initial claim. There are, in particular, some touchstone concepts that Ramchal addresses in ways that simply don’t align with the Tzfas approach.

For instance, when Ramchal (in chapter five) describes the value of Torah study, he doesn’t talk about its segula-theurgic power (i.e., how its study might invisibly influence the cosmos) - an approach common among kabbalists. Instead, Ramchal celebrates how Torah study can, in a very practical sense, protect us from a dangerous loss of focus in our mission.

Another obvious “un-Tzfas-ism” in the book is Ramchal’s discussion of defining the ideal intentions that should drive our actions (i.e., l’shma). Kabbalists would famously focus l’shma on specific partzufim or on theurgic executions. By contrast, the categories and context Ramchal used in his description (chapter 16) are purely natural and perfectly in sync with a traditional, pre-Ari worldview.

Similarly, contrast Ramchal’s instructions for the proper mindset during prayer from chapter 19 with the kabbalistic שביתי charts and mystical diagram posters commonly found in synagogues as prayer aids. Here, however, is how Ramchal would have us focus:

“The core fear (of heaven) is fear of His greatness. For a man must think about Him as he prays or performs a mitzva that his is praying or performing a mitzva before the King of all kings…”

Finally, when discussing kedusha (holiness) in chapter 26, Ramchal quotes the midrash (Rabbah 82): “The avos [‘fathers’] are the chariot” and explains: “That the Divine Presence rests on them as it rests on the temple.” This simple illustration is plainly different from some more popular kabbalistic interpretations of the midrash (which are perhaps best not repeated without urgent cause).

A Few Exceptions

It is true that Ramchal directly quoted Zohar at least once - in chapter nineteen: "איזהו חסיד המתחסד עם קונו". But that hardly served to advance any ideologically kabbalistic principle. Instead, it simply amplified a common idea based on Avos (1:3): “Do not be like a servant serving his master for reward, but like a servant serving his master for no reward.”

By contrast, when the Ari addressed this same issue, he advocated explicit efforts to divert prayer and mitzva observance in the service of theurgic goals (see the notes on page 356 of R’ Avraham Shoshana/Ofeq publication of the Guenzburg edition, 5759). Specifically:

אין ענין זה מתקיים אלא במי שיודע כונת התפילה והמצות ומכוין בעשייתם לתקן עולמות העליונים וליחדא שמא לקב"ה עם שכינתיה

One would be hard pressed to imagine that two such different approaches sprang from a single source.

To be sure, there are a few ideas scattered through Mesilas Yesharim that can’t be easily traced to mainstream Torah sources and, in fact, sound vaguely theurgic. This passage from the first chapter is an example:

“For if a man is drawn after this world and distances himself from his Creator, he will be corrupted and will corrupt the world with him [but otherwise] he will be elevated and the world itself will be elevated with him. For it is greatly elevating for all creations when they serve a perfect and sanctified man.”

Nevertheless, Ramchal himself attributes this idea to Koheles Rabbah (7): “Take care so you shouldn’t become corrupted and destroy My world.”

Also in the first chapter, Ramchal wrote:

“…as Chazal taught us, that a man was not created except to take pleasure on God [להתענג על השם] and to receive enjoyment from the shine of His presence.”

Honestly, I’m not even sure I understand what that means. But I certainly can’t imagine where it could be found in Chazal. In that context, I believe it’s highly significant that the corresponding text in the recently discovered and published first edition of Mesilas Yesharim (originally written in the format of a conversation between a chassid and a chochom) is phrased:

“…My opinion on this [דעתי בזה] is that a man was not created…”

“Chazal” are not invoked.

You not seeing Kabalistic ideas is because you expect kabalistic ideas to be super esoteric sounding. Really kabalah is nothing more than the guide to get close to Hashem. Since it is very nuanced, it can get really, really complicated and those details are the fine print. But the Ramchal had the uncanny abiltiy to simplify things. There is not a word that is not found in his other more kabalistic seforim

'But I certainly can’t imagine where it could be found in Chazal'. Many had asked this question, but the source seems quite obvious:

צדיקים יושבים ועטרותיהם בראשיהם ונהנין מזיו השכינה.

Y. Leibowitz