Tzedaka Emails and the Criminal Misuse of Public Space

What the ancient pashkivil might possibly teach us about modern "frum" marketing

It’s easy to lose track of the full impact trends and behavior have on the world if you’re regularly exposed to them. But revisit a community after a long absence, and it slaps you in the face. My recent first trip to Israel in 40 years reintroduced me to the many delights of the internet of the 19th Century: pashkevilim.

A pashkevil is a printed poster that’s pasted to public-facing walls as a way of attracting attention to causes or events. In certain communities, if you’re pushing for (yet another) smartphone ban, more votes for your favorite political party, or attendance at a high-profile funeral, then the pashkevil is the marketing medium of choice.

The problem that struck me after my recent exposure to the practice was not the posters themselves (sidewalk traffic normally moves too fast to read them anyway), but the walls on which they were pasted.

Who owns those walls?

Did the owners consent to that particular use?

Does halacha even require consent?

Who takes responsibility for the hard work and expense of removing old posters?

What role might civic bylaws play?

I could imagine one making the argument that, even if the first posters on a particular wall were attached illegally, once public access was implicitly permitted, adding new posters is no worse than taking a well-trodden shortcut through someone’s backyard (see Bava Basra 99b). Although, when you consider the ongoing maintenance costs, even that comparison isn’t obvious.

But that wouldn’t explain the countless yellow Chabad “melech hamashiach” posters that feel like they’re plastered on to every highway overpass and public street sign through the entire country. As those are nearly always the very first ad hoc posters in their locations, the principle from Bava Basra doesn’t apply.

Since the pashkevil practice isn’t exactly new - it’s probably been in use for at least a few centuries - I assumed that the halachic issues would be discussed in the teshuva literature. I looked. And I asked around. But no one could find anything. Perhaps one or more of my esteemed readers has some thoughts on that.

But this brings us to the real subject of this article. The problem of paskevilim is all about people trying to promote their businesses and ideologies through the misuse of private property. Well there’s a modern variation involving people trying to promote their businesses and ideologies through the misuse of private property.

That would be email spam.

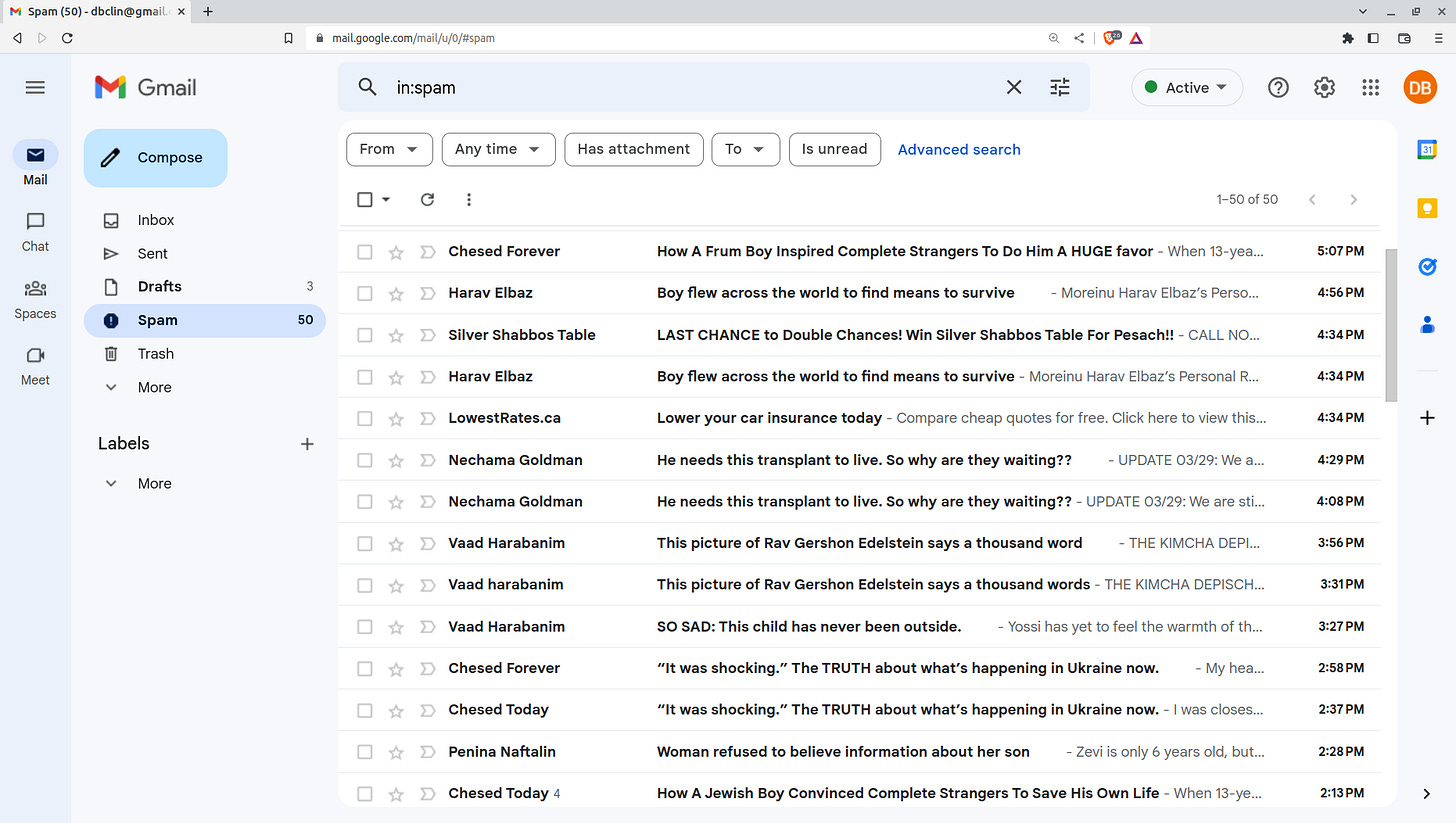

Until recently, I would often receive more than 80 unsolicited (and illegal) emails promoting tzadaka campaigns…EACH DAY. Here’s what the Spam folder of my main Gmail account would usually look like:

Note how consistent the style of the individual message displays was, but the email origin identities varied. And note also how there were more than a few matching subject lines.

The first general point to make about unsolicited email is that it’s illegal. As ChatGPT tells me:

Under the CAN-SPAM Act, sending spam emails to US-based email addresses is not illegal in and of itself, as long as the emails comply with certain requirements. For example, the emails must include a valid physical address of the sender, a clear and conspicuous identification that the message is an advertisement or solicitation, and a clear and easy-to-use mechanism for the recipient to opt out of future emails.

However, if a sender violates the requirements of the CAN-SPAM Act, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) can pursue enforcement action against the sender, which can result in significant penalties. The penalties can include fines of up to $43,280 per email message, as well as other penalties such as asset forfeiture, injunctions, and other legal remedies.

The next thing is that this isn’t just a דינא דמלכותא דינא issue (with all the associated ambiguity). There’s real and brazen theft going on.

I’ll explain. There is a hard, financial cost to transmitting every data packet across a network that someone has to pay. Processing a single email message which might consist of a few thousand bytes of data won’t make a measureable difference. But spammers - like the “tzedaka” organizations behind many of the messages I was receiving - probably send out millions of emails a day.

Those messages are sent through third-party mail servers (either Pulseem or Robly for the most part) whose service agreements require adherence to specified conduct. Among other things, they forbid adding email addresses without the owners’ consent. When an organization ignores those rules, they’re using their mail server’s resources without permission. And the resulting network transfer costs are paid by the mail servers as part of their ISP bills.

But all that extra bandwidth is also seen at the other end. Or, in other words, the ISPs used by the users who were targeted by all the spam. A major ISP like Comcast might easily have thousands of customers on “tzedaka” lists. And they, too, must share the costs. Those costs are, naturally, passed on to their customers in the form of higher monthly charges.

Network bandwidth is only one cost category associated with spam, but I think you get the picture. The point is that this isn’t a benign “victimless” crime. And it doesn’t instill confidence in the general reliability of the people behind these campaigns.

Still, I’m eager to see if anyone of you can add clarity to these issues from a halachic perspective.