Torah Observance and Financial Stability

How observant communities can't possibly survive...but do anyway

I recently reminded myself of something I’d read many years ago in the 19th Century sefer, Niflaos m'Toras HaShem - and it’s a perfect fit for this publication. The author was the Warsaw businessman (and former Volozhin student), Rabbi Tzvi Hirsh Shloz. For those who track these things, R’ Yitzchak Elchonon Spektor of Kovno was among those recommending the book.

In chapter 88 of the book’s second volume (the key two pages are sadly missing from the Hebrew Books version), Rabbi Shloz observes how the loyal observance of the Torah’s laws would, by any rational calculation, financially cripple anyone who tried it. The fact that the Jewish people - through their centuries of existence in Israel - didn’t collapse, is overwhelming testimony to the guidance of a Higher hand.

Basing himself on an observation of the Kuzari (2:56), Rabbi Shloz describes, in practical terms, just how much mitzva observance would have cost the Jews, both in terms of lost income and lost productivity. Here’s how that would look:

Lost Income

Consider how the Jews living in Israel for the first thousand years or so of our national existence lived and worked within a mostly agricultural economy. Land ownership was the major source of wealth, and everything from simple sustenance to commercial trade probably depended on farm work of one kind or another. There were artisans like metal workers, but I suspect there weren’t many whose primary income came from such pursuits.

Now consider how profiting from nearly all farm produce was prohibited every seven years during Shemita (Vayikra 25:4), and again every 50th year for Yovel (Vayikra 25:10). Anything that did grow during those years would be made freely available to the poor. That might eliminate something like 16% of a family’s lifetime income.

But even during the 42 years from each 50-year cycle where crop profits are permitted, you’ll still have to give up a tenth to a levi for maasar rishon (Bamidbar 18:26). Another tenth will go to poor people for two out of every seven years. Between those two, you will have “lost” another 11%.

Beyond all that, another tenth (maasar sheni - see Vayikra 27:30) of the produce of four of every seven years must be eaten in Jerusalem. That produce does belong to you, but it’s value is reduced because of its restriction. The same goes for one of every ten cattle born to your herd (Vayikra 27:32), which also must be eaten in Jerusalem. Add on the “loss” of 24 priestly gifts, first born animals, bikurim, and offerings that come up from time to time - like those brought by women after each birth.

All told, we would have been left unable to enjoy at least 30% of our “pre-tax” income. Pre-tax? Yup. Because according to the Rambam (הל’ מלכים ד:ז), Jewish kings had the right to collect 10% of all grain, fruits, and animals.

So our income losses are starting to creep up towards 50%…

Lost Productivity

Which brings us to labor restrictions. Because for a significant proportion of our adult lives, we are unable to work. Some of those restrictions (Shemita and Yovel) relate specifically to farm labor. But others (Shabbos, Yom Tov, Rosh Chodesh, etc), the limitations are universal.

As with income, Shemita and Yovel will limit the time we can work our farms by around 16%.

But think about the mitzva to ascend to Jerusalem for the three festivals (Devarim 16:16). People were expected to travel from as far away as 15 days’ journey. That would mean 15 days up, 15 days down, with more time spent in Jerusalem…and all repeated three times each year! Effectively that means many Jews lost another three full months of work - or 1/4 of their lives - for this one mitzva. That will give us an adjusted figure of around 28%.

I won’t count the days of Yom Tov themselves, because they’re effectively already included in the mitzva of attending festivals. But I will count lost days for Shabbos observance for another 11%.

Where did I get that number? I took the total number of days in a single 50-year cycle (18,250) and divided those by the seven days of the week (~2600). I then subtracted the Shabbos days that would fall during a Shemita, Yovel, or regel cycle (~ 550). The new total (2050) would be 11% of 11,250. Of course, I also deducted overlapping days from our festival attendance count to give us the adjusted figure of 28% above.

As Rabbi Shloz observes, it seems that Jews took time off from work on Rosh Chodesh, and that, like us, they sometimes celebrated two days in a single month (see א שמואל יט:יח). That’ll cost us another 5%.

Which, if we add it all up, would mean that Jews were allowed to work around 60% less than they’d normally expect. And that they’d lose around 30% of their pre-tax income.

Of course, we know that observance wasn’t always universal. “Perhaps,” you might argue, “Jewish society only avoided economic disaster because only a small minority even tried to keep those laws.” Well that might have been true during certain periods - there’s plenty of evidence, for example, that convincing everyone to come to Jerusalem for the festivals was a perennial challenge. But, working with traditional sources (and even non-traditional sources that don’t rely on baseless speculation), you’ll have an uphill battle convincing me that there were no decades or even centuries through those many years when observance wasn’t the rule rather than the exception.

And in any case, we’ve all seen similar Guidance with our own eyes, haven’t we? What else satisfactorily explains how our own communities survive and even flourish despite many of the same labor restrictions and enormous private school tuition and other unavoidable communal costs?

And by “avoidable”, of course, I mean costs that can’t be avoided. As opposed to crazy materialistic standards and luxury weddings that could easily be passed on.

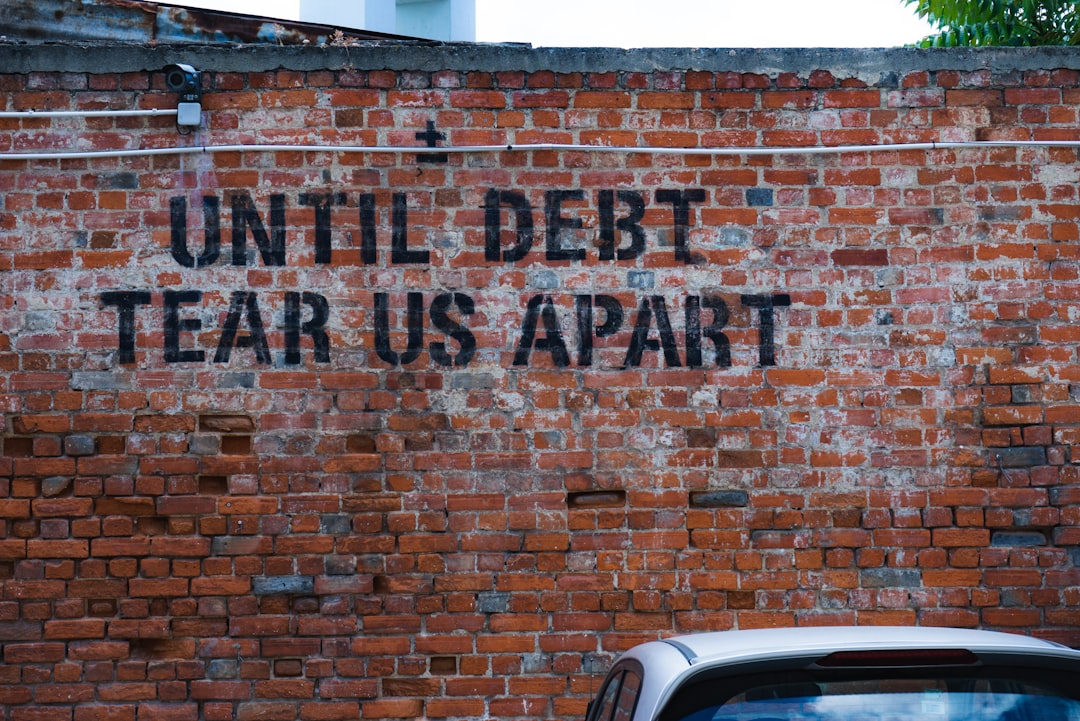

Facing Financial Crises

Rabbi Shloz adds one more important point to this chapter. Referring, presumably, to the Panic of 1873, he gives some valuable context to the laws of Shemita.

The 1873 crisis (arguably) began when financial markets - and particularly lending markets - were spooked by defaults. Creditors suddenly called in their outstanding debt, leading to cascading failures, as more and more leveraged positions failed.

Rabbi Shloz described how princes and aristocrats were ruined overnight. In some cases, families and institutions had been running up devastating debt for generations, always assuming that “the market” would sustain them forever. But, for many, it was a lie. Some would do anything, no matter how unsound and desperate, to maintain their status.

But the Shemita system, Rabbi Shloz tells us, with its seven year caps on loans and 50 year limits on property transfers, is built to prevent such excesses. It would be simply impossible to amass those levels of debt when living with such time restrictions. Or, in other words, Shemita is a safeguard against extreme irresponsibility.

Well.... the Jewish financial history is yet to be written and a good thing that it hasn't been, ודי למבין.