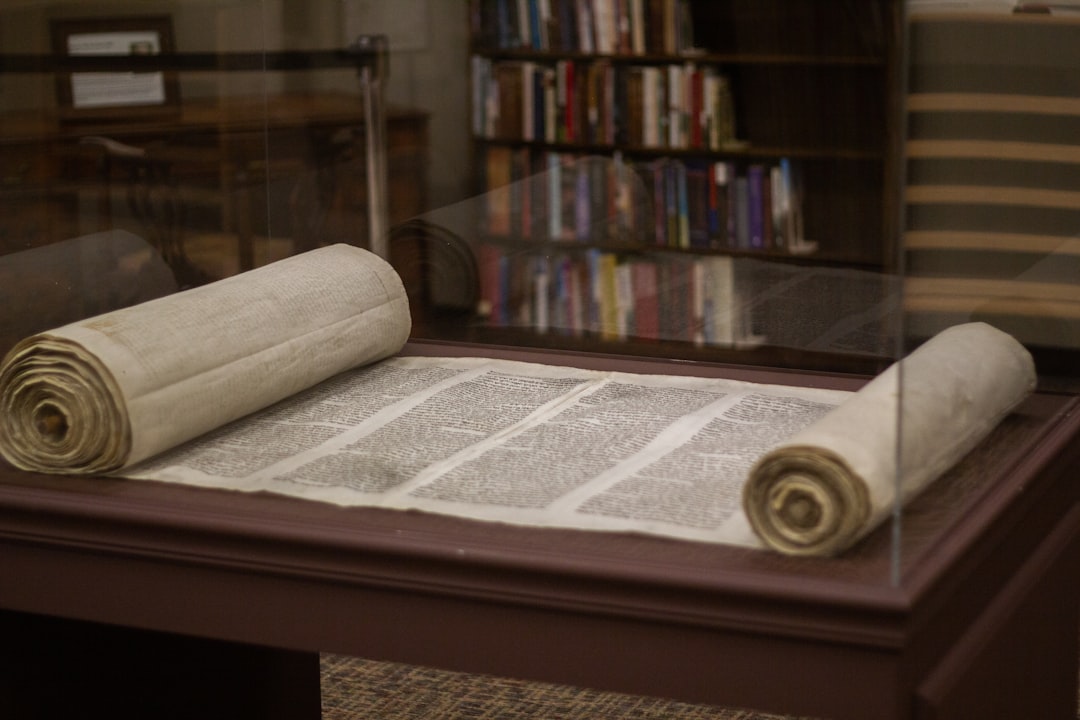

Is the Text of Our Torah Scrolls Accurate?

The consequences of the historical confusion over the masoretic Torah text.

From the moment our nation received the Torah at Mt. Sinai, knowing and maintaining the precise written text of the Five Books in our own Torah scrolls was critical. That the exact text of the Written Torah is an essential part of the "package" is clear from a number of statements of Chazal, including Gemara Megila 19a:

“The Holy One showed Moshe dikdukei Torah and dikdukei scribes (דקדוקי תורה ודקדוקי סופרים)”

...on which Rashi commented:

Dikdukei Torah: multipliers (ריבויין) like את and גם. dikdukei scribes: that later scholars analysed the words of earlier scholars

Without a complete and reliable text, trying to draw inferences of this sort would be futile. Even accurately identifying minor variations like “full” or “lacking” spellings (יתירות וחסירות) is, as we see from the Pirush HaRosh to Nedarim 37b, referenced through the words ויבינו במקרא (Nechemia 8:8).

These details are important enough that the Gemara in Sanhedrin 99a equates the denial of even one “dikduk” (according to Rashi, full or lacking spelling) to disgracing the Word of God.

In fact, authorities like the Ramban (in the introduction to his Chumash commentary) taught that the entire text contains subtle allusions to God's names, presumably using the base text of the Torah in non-narrative ways.

Naturally, if our text of the Torah isn't accurate, that style of inference will be lost.

The problem

While we don't doubt that the Torah scrolls written and left to us by Moshe himself were the letter perfect record of God’s instruction, there long seem to have been questions surrounding the status of the later copies. For example, we find a remarkable passage in Avos d'Rabbi Noson (34:5 - and echoed in Bamidbar Rabba 3:13):

Why did Ezra use dots ("נקודות" over the letters in some Torah passages)? This is what he was saying: If Eliyahu comes and says to me 'Why did you write this (spelling)?' I will say to him '(That's why) I added dots above (that word)' and if he says ‘You did well writing this way' I'll remove the dots.

This suggests that Ezra himself was unsure of the correct text for at least that significant handful of verses that include dots. I should note that The Taz (שו"ע יו"ד רע"ד ס"ק ז) hints to the existence of an alternate text in Avos d'Rabbi Noson.

In another interesting revelation, the Gemara in Shabbos (104a) tells us that, for at least some generations, we were unsure of how certain letter shapes (מנצפך) should be written, and required prophecy to remind us.

In later generations, as we see from Kiddushin 30a, to at least some degree we lost our collective knowledge of chasaros and yesaros:

They were experts in chasaros and yesaros but we aren't experts.

This likely means that the sifrei Torah used in those later times were assumed to be incorrect.

The problem of chasaros and yesaros is most definitely still with us. The universally accepted text found in all modern Chumashim contains discrepancies with versions used by at least some rishonim (see the Rashi to older printings of Devarim 6:9 and note his spelling of מזוזת).

This problem is so real that the Rema (או"ח קמ"ג ד) rules that, in some circumstances, you should not bother taking out a replacement scroll when encountering a definite error in a scroll Torah during krias haTorah. This is because the replacement is unlikely to be any better than the first.

Are we talking about just a few doubtful spellings or are there hundreds spread throughout our Chumash? From the above sources, it's hard to say. But the author of Minchas Shai, in his introduction, suggests that the Torah scrolls available in his time were completely riddled with errors and conflicts.

Despite the fact that the Minchas Shai was written long after the introduction of printed chumashim - which allowed for standardization of texts - the author's efforts to establish the correct text required enormous efforts, involving both logical analysis and comparisons of many existing copies. And even once his work was complete, he still wasn't sure he'd been perfectly successful.

The consequences

So what is the practical impact of not knowing the authentic text of the Chumash? Well for one thing, we can no longer be absolutely sure of the accuracy of any of the many derashos derived from subtle textual details like chasaros and yesaros - even if their halachic conclusions are not in question.

We will, of course, also lose any connection we might otherwise have had with Ramban's "Torah filled with the names of God". Further, those (few) individuals who value the results of "Torah codes" research should be deeply disappointed to learn that their equidistant spacing system is thoroughly unreliable.

But perhaps the biggest victim is the eighth of the Rambam's core principles of faith which, especially according to Rabbi Kapach's widely respected edition, requires a perfectly accurate text of the Torah:

והיסוד משמיני הוא תורה מן השמים והוא שנאמין שכל התורה הזו הנמצאת בידינו היום הזה היא מתורה שניתנה למשה